0%

Stories are the backbone of great games. In Part 1 of our Narrative Design series, Blind Squirrel’s design team breaks down the fundamentals of building worlds that players want to live in.

Blind Squirrel Design Department: Narrative Design Series

Part 1: Intro to Narrative Design

Welcome to our inaugural blog post on narrative design! My name is Mimi Black, a narrative producer, narrative designer, and writer at Blind Squirrel Games (indie games… where everyone keeps a large bucket of hats near their desk), writing in conjunction with our Creative Director, Haydn Dalton, and our Lead Game Designer, Nathan Sumsion, with editing by our Marketing guru, Katherine Clare.

When a series of blogs over narrative design was suggested, two thoughts crossed our minds: We have so much to share! And, who’s going to listen to us?

When you think of the big hitters of game narrative, Blind Squirrel Games probably doesn’t cross your mind. Individually, our design department has a robust game history, from Darksiders to Disney, Star Wars to Star Trek, as well as other ventures such as published novels, plays, films, and even poetry. As a studio, we’ve worked on a lot that you may know, but there’s a lot that we can’t talk about. The reality of being an indie work-for-hire studio is that you do a lot of work on games, pitches, and consultations that aren’t advertised or discussed. (And then there’s the work that never sees the light of day. Anyone in the game industry knows this is just a frustrating reality of the business.)

We realized that our Blind Squirrel perspective is fairly unique (for example, a future post about working with others’ IP), our experience diverse (I have jumped genres from sci-fi to horror to dystopian in the past month alone), and we do have much to share that is hopefully both interesting and useful. In this series, we will be diving into narrative design in general, from the perspective of a co-development studio, when working with partner IP, and more.

But for now, we’re starting with the basics…

What is Narrative Design?

Narrative design is the way in which a story is conveyed or implemented in a game. There are many ways to do this, and game narratives are inherently unconventional forms of storytelling. But they all have one thing in common: interaction.

Games are the only form of narrative entertainment that requires you to be active.

Books: passive. Films: passive. Theatre: passive. Music: passive. You are reading, watching, or listening (And to all the LARPers and escape room devotees about to type a strongly worded reply, I hear you, but I am talking about mainstream art forms – do not strike me).

In games, you are DOING. Narrative design requires you to weave story elements in and among game mechanics to create a sequence of events that form a synergistic, interactive story.

Types of Game Narrative

Depending on who you ask, there are more or fewer types of game narratives than the ones listed here, and many developers use different terms (although linear and branching are pretty standard).

Linear

Linear narratives are the simplest form of narrative in terms of scope. They are like film narratives. Players get the same experience and story every playthrough, with only some subtle variations here and there. There’s no branching, no out-of-order side quests, and very rarely is there more than one ending.

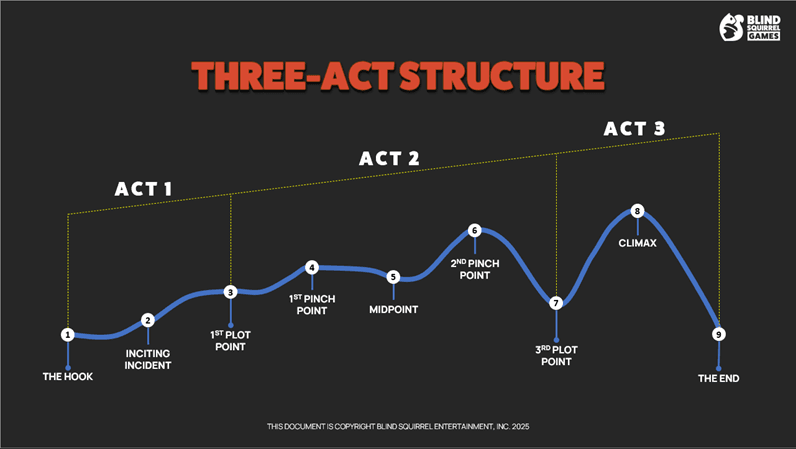

Because linear narratives are close to traditional forms of storytelling, it can be useful to use a three-act structure framework. It typically looks like this:

This is just one of many narrative frameworks out there. This is the most popular, tried-and-true framework for Western forms of storytelling, from Lord of the Rings to Star Wars (my examples used below – along with the game Bioshock) to Final Fantasy VII to Red Dead Redemption 2 to all the Telltale games. But there are other formats that you can follow. Probably hundreds. A lot of East Asian narratives follow a four-act structure called kishōtenketsu. Or, there’s the Nicaraguan Robleto story structure, which uses five stages. Many cultures have their own structures that they find most satisfying. The three-act structure below is the most cinematic structure as it is good at putting audiences (or players) through a steadily paced, rewarding narrative packed with suspense and emotional payoff.

For those of you who haven’t played Bioshock, I am adding the analysis at the end of this blog as an appendix.

ACT 1

The Hook

A scene or event that hooks the audience.

In A New Hope, we’re thrust into a battle, meet Darth Vader, and see two droids launched into space… It makes us ask, what the hell is going on? I gotta keep watching and find out…and in the case of games, I gotta keep playing. The Hook can be tricky when applied to games. Sometimes it is combined with the inciting incident. How do you make a hook interactive? Bioshock does this with a brief cut scene showing our plane crash into the ocean and then makes us swim to a mysterious lighthouse. (That is my one and only Bioshock reference before the appendix at the end. I’m sorry I spoiled the first two minutes. Enticing, though, no?)

Inciting Incident

The event that puts the plot in motion. We're not fully immersed yet, but the protagonist’s life will change forever if they engage (they will).

Bilbo leaves the ring with Frodo. Luke buys R2D2 and C3PO.

1st Plot Point

The point of no return. The world or character has changed. Up until now, the protagonist may have been passive, but not anymore.

Frodo leaves the Shire. Luke leaves Tatooine because Aunt Beru and Uncle Owen are dead.

ACT 2

1st Pinch Point

The first major turning point that moves the plot forward, highlights the antagonistic forces at work, and sets up the midpoint.

We meet Han Solo and have to flee the stormtroopers on the Millennium Falcon. Frodo gets stabbed by a ringwraith and is taken to Rivendell.

Midpoint

The big twist that shows us what we’re really up against. The moment of truth, where everything changes.

Frodo volunteers to take the ring to Mordor. The Death Star and its prisoner, Princess Leia, are revealed – it’s now a rescue mission.

2nd Pinch Point

Shows what’s at stake and highlights antagonistic forces while setting up the 3rd plot point.

The trash compactor is about to crush everyone. The fellowship is forced into the mines and – SPOILERS (although, if you’re reading this blog and don’t know what I am about to tell you, you’re probably never going to watch/read Lord of the Rings anyway) – Gandalf dies.

ACT 3

3rd Plot Point

A false victory followed by a low moment. Often, the protagonist’s darkest hour. A transformative moment.

Frodo gets to Lothlorien (yay!) and finds out he must bear the ring alone and leave everyone (bummer). Luke and the gang make it to the Falcon (yay!) and then Darth kills Obi-Wan (bummer).

Climax

The final confrontation! The big show down! This can be a building scene or a few scenes, but there’s always a climactic moment that determines the conflict’s outcome.

Luke uses the force and destroys the Death Star. Frodo is attacked by Boromir and runs away solo as his friends are captured.

The End (Resolution)

The calm after the storm, when we see where all the pieces have fallen.

Luke and Han get medals. Frodo and Sam take off.

The thing about games, though, is that they are a lot longer than a film, which is what this structure was initially devised for (by screenwriter Syd Field). In a film, these plot points are spread out over the course of about 2 hours, give or take. In a game, they’re spread over 8, 20, even 101 hours (Persona 5 Royal), so a lot of gameplay (and plot) needs to happen between these plot points. The important things to remember are that action should be rising and your player: • Always needs a goal (no matter how small – and they need to be achievable) • Performs actions via mechanics • Faces obstacles • Progresses forward (in skill and story)

Branching

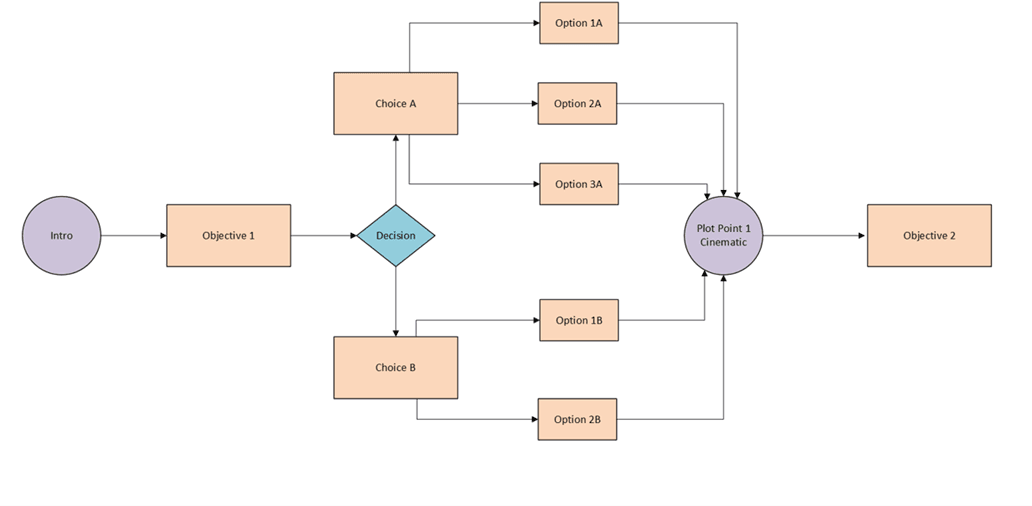

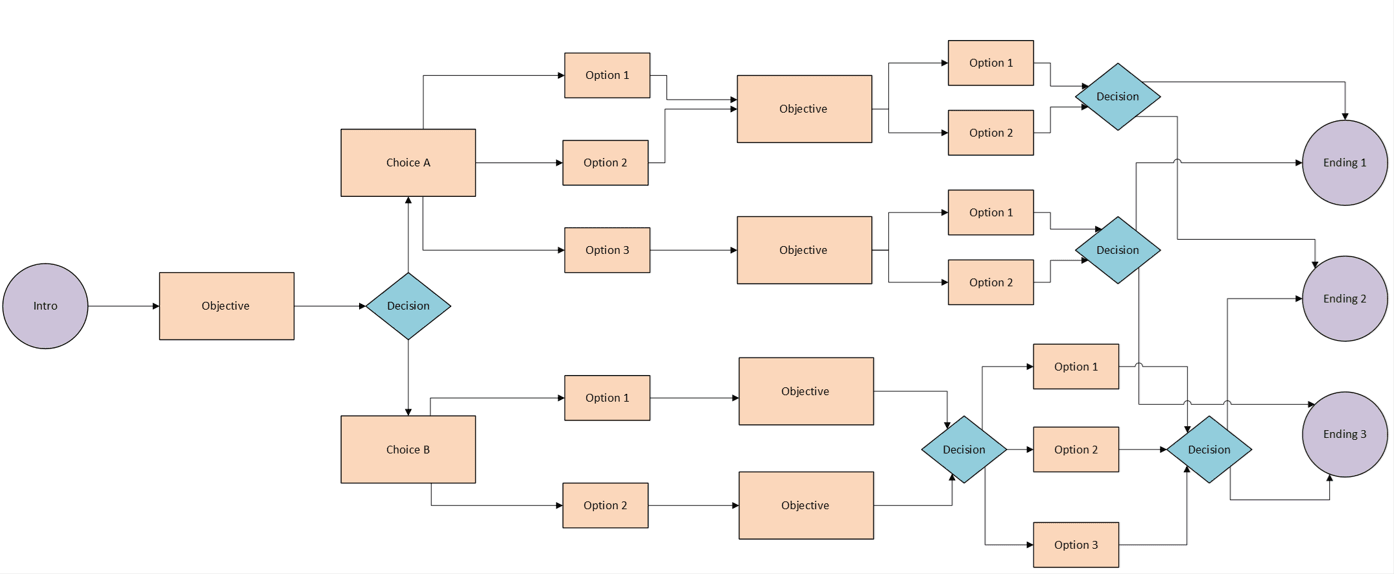

Branching still has a main storyline, called the critical or golden path, which can also use the three-act structure model. However, instead of a single linear path, there are multiple ways players can branch off that golden path. This gives players more agency. Whereas linear gives no real choice, branching gives (seemingly) many, making the game feel tailored to the player. Choices matter and they have consequences. (If they don’t, be prepared for an angry mob.)

In most branching narratives, players complete a chain of quests that then converge at specific points before branching off again. The journey to those main plot points is what differs. Sometimes there are small differences, like conversations with NPCs, and sometimes there are entirely different quest lines.

Usually, there are several endings. But despite seemingly endless choices throughout the game, most branches funnel into one of a few endings. Because….

Making games is EXPENSIVE. Every branching choice means more VO to record, new environments to build, new animations to craft… more time, more money. Before you start writing your branching epic, make sure you know your game’s budget, time restraints, and personnel limitations.

Branching can look like this…

Or this…

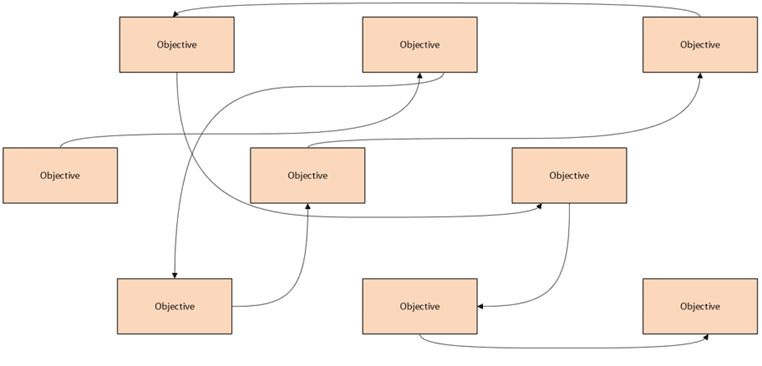

Open

I like to call this “BYOS” (Build Your Own Story). Some call it an amusement park. This is for sandbox games, MMO’s and RPGs with quests that can be played in any order. From World of Warcraft to Skyrim to Cyberpunk 2077, it’s branching narrative on steroids. In branching narratives, you can choose to go from A to B to C or E to F to G, with both paths leading you to H. In open narratives, you can go from C to H to A to Z. The only thing stopping you from initiating a task or quest is usually your skill level.

(Designers often use skill levels to prevent players from experiencing something too soon. Because even open narratives generally have a golden path, we need to find some way to prevent you from seeing your best friend betray you before you’ve even met her. This is called GATING. We know that once you’re at a certain level of skill, or if you have had a run in with a certain NPC, that you’re free to move onto other areas or quests without screwing up the story.)

Do games like Minecraft and The Sims have a narrative?

They have a narrative wrapper - an underlying (overlying?) idea that informs the world and events that put you there.

But as far as an actual narrative, this starts getting into narratological discussions about emergent narrative (the narrative players experience and create through their actions) and the discourse developers implement in game (the story we’re trying to tell) and that’s way too much esoteric rambling for this post.

Environmental (Implied Narrative)

Some games don’t allow for typical narrative components but imply a narrative through the environment.

We’ve seen this with games like Fortnight, PubG, or Overwatch. The world, its characters, their abilities, or the game’s setup imply a story. This can also be achieved through supplemental materials like trailers or content often found online.

Our new original IP, Cosmorons, is an arcade-inspired sci-fi shooter. You play as robots called drudges who are sent on an endless mission to conquer the universe on behalf of their mysterious overlords. Implementing a major story arc and cut scenes, hiring actors for VO, and loads of bespoke animations were out of scope. So, we focused on telling our retro sci-fi satire on corporate bureaucracy and empire through the player lobby:

• Satirical motivational posters • Various props such as a water cooler and an oil dispenser that looks like a coffee maker • TVs everywhere that play ads for new real estate ventures, as well as products to buy • Safety announcements that are completely not safe at all • Recycling bins and trash chutes for spare body parts

We also made an intro video that feels like a trailer for a 1950s sci-fi film but showcases the drudges' ineptitude and the impossibility of their mission, alluding to the core loop of the gameplay.

All these elements imply a larger narrative that will be revealed down the line and allows players to come to their own conclusions about the universe while immersing them in a fully formed backstory and tone.

What Makes a Good Game Narrative?

A good game narrative is interactive.

If I wanted to watch a bunch of cut scenes, I’d watch a film. I want a tangible, interactive story with as much agency as possible. When crafting a game narrative, ask yourself at every step, "Is there a way to tell this through action?" (Then ask, “Can we afford that?”)

A good game narrative is harmonious with the game mechanics and action.

If your game features a flying mechanic, don’t set it in a network of caves. Set it in the sky.

There are exceptions to this, of course. Designers love a challenge, and putting two opposing things together can create something new and interesting (for example, zombie games benefit from tight corridors, dark spaces, and blind corners. They create suspense. But then Dead Island comes along and does the opposite). It goes back to that old adage, you have to know the rules to break the rules. Know why the twist works and make sure it’s satisfying (Dead Island is unsettling because the zombies are fast, and due to the open spaces, can come from anywhere – and you can see them all coming straight for you in the bright light).

The important thing is to meet and exceed player expectations. People get frustrated when they’re given a mechanic they can’t use to its full potential or when it does not make sense for the world.

A good game narrative evokes emotion.

Players should feel emotionally invested in the story. Many factors contribute to a narrative's emotional power, but a good starting point is to ask yourself how you want the player to feel at every stage. Scared? Sad? Angry? Powerful? A great narrative never stays at the same emotion for too long. Weave in the highs and lows.

A good game narrative creates suspense.

This doesn’t mean every game should be a thriller. It means the player must always want to know what happens next. The moment they don’t, they stop caring, which often means they stop playing. Suspense is formed by raising questions that demand to be answered or by wanting to keep performing actions to see what the result will be.

Because narrative should be aligned with the game mechanics, the earlier the narrative designer gets involved, the better.

Narrative as an afterthought is a veneer that many players see through. They sense the gaps and the brittle patchwork where you welded two things together that didn’t quite fit. When game design, mechanics, world building, etc, are synergistic with the narrative, players know. This is why games like Bioshock, Last of Us, or Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time are highly lauded by critics and players alike. For example, in Zelda, the Ocarina of Time and its time travel mechanic are a vehicle for telling Link’s story as well as impacting gameplay – they even named the game after this one crucial mechanic.

This isn’t always possible. Sometimes you’re hired after most of the core development is done, or you suddenly have to overhaul an entire story for legal reasons, etc. Then it becomes like those recipe challenges where they say, “here’s an onion, five sardines, vanilla ice cream, and a boot, now make me a Michelin-worthy entrée.” It’s your job to weave seemingly disparate pieces into a cohesive whole. It’s rarely as good as when the narrative develops in tandem with other departments, but if you’re creative enough, you can get pretty close.

What Goes Into Narrative Design

Because Narrative Design requires a physical space, interaction, player agency, and more sensory feedback than many other mediums, the toolset narrative designers work with is vast.

In a future post, we will delve into the depth of narrative design in more detail (there’s a lot!), but here are some key components:

Environmental Storytelling

Touched on above, this is one of the best ways to integrate story. Every piece of set dressing, art, ambient dialogue, found objects, and even the level design, contributes to the narrative.

Many players don’t want to stop and watch cut scenes or go through endless dialogue trees, so it helps to be sneaky with narrative: (Literal) writing on the wall (graffiti, signs, posters). A desk scattered with disturbing drawings and journal entries. A castle with severed skulls piled high. A group of gossiping NPCs whispering about werewolves and kings… There is a lot to convey through the environment.

Mechanics & Core Loop

Since games are an active art form, mechanics are your bread and butter. Make sure your narrative marries with the mechanics. The core loop is the essential ingredient that all games start with. It’s the cycle you repeat throughout gameplay:

(Explore>Battle>Earn>Upgrade)

Make sure your narrative works with the game’s core loop. Coming to the designers with a narrative about a pet store kitten trying to find a home probably isn’t going to work with the above core loop…unless you’re designing Killer Kitten: Pet Store Escape.

Outlining, Wireframing & Dialogue

Outlining: When developing the core story, start with an outline like the three-act structure. As side quests are written, they can follow a similar outline format but on a smaller scale.

Wireframing: Games contain a lot of content, and keeping track of the order of quests, how they connect, where they branch, etc., is best done using wireframing, sometimes called a node map. (See the images in the branching narrative section for examples.)

Dialogue: Dialogue can convey backstory, reveal character and important plot points, but it should be used sparingly for most game genres. People want to get to the action. Well-placed, well-written dialogue is a tremendous asset. Bad, verbose, poorly placed dialogue can annoy players and sink your momentum.

Themes and Tone

A theme is a central, recurring idea that underlies the entire game. If you have a theme (or a couple), keep asking yourself whether what you’ve written or designed supports the theme. If it doesn’t? Cut it or change it. Examples of themes: blood is thicker than water; corruption of justice; love conquers all.

Tone is a mood that permeates the entire game. A cute slapstick-y game for kids might have the tone: Saturday Morning Cartoon. For our game Cosmorons we had two: “Irreverent slapstick” and “satirical, retro sci-fi.”

Cut Scenes

Cut scenes, or cinematics, are animated, scripted sequences that are like traditional film scenes. They can be great for heightening emotion and conveying information you don’t want the player to miss, but they should be used sparingly. The player is watching the action rather than playing it, which is not what this medium is about. Too much time in passivity means players get frustrated or bored.

Conclusion

Narrative design isn’t just about crafting compelling characters or memorable dialogue; it’s about building the scaffolding that holds a game’s emotional and thematic weight. Now that we've laid the groundwork and defined what narrative design is, it’s time to dive into how it actually gets made. In the next part of our series, we’ll walk through the full arc of narrative development, from those first sparks of inspiration to the final polish pass. Whether you're plotting a character arc or stitching together a world bible, every story starts somewhere. Let’s explore the process that brings it all to life.

Mini Case Study: Bioshock Three-Act Structure

Even though Bioshock fits the three-act structure very well, you could argue some of the plot points here. I had to really think about a few of these. And that’s because a game is so much longer than a film, and you need far more exciting turning points to keep a player engaged. So even though I’ve identified what I consider to be the key points that fit into the basic cinematic structure, some might disagree and feel other moments better fit the structure’s points… if you do, let us know! FIGHT ME! (Would you kindly?)

Also, this is only for the non-meanie path, where you save the little sisters, not harvest them.

ACT 1

The Hook

It’s 1960 and you’re on a plane, admiring family photos and a gift from mom and dad (with a note that says not to open, “would you kindly” – foreshadowing). The plane crashes into the ocean, and you must swim to a massive art deco lighthouse on an island.

Inciting Incident

You meet Atlas (via radio), who says he's going to help get you out of Rapture. Faced with a hostile world and the unhinged splicers, he convinces you to take your first plasmid, forever altering your genetic code and giving you superpowers.

1st Plot Point

Atlas tells you about his family that needs rescuing. He's been cut off from them. He needs you, Jack, to reach them in Neptune's Bounty.

ACT 2

1st Pinch Point

You get to the submarine that holds Atlas’s family, but before you or Atlas can rescue them, Ryan blows it up, killing all inside (allegedly).

Midpoint

You find Andrew Ryan, and he reveals that you are not who you think you are: you’re actually a genetically engineered sleeper agent who responds to the words “would you kindly” – Atlas’s signature phrase. You kill Ryan and take his genetic key so you can finally let Atlas into Rapture. When you do, he reveals another shocking twist – he is actually Ryan’s nemesis Frank Fontaine. He had you created to kill Ryan and aid in Fontaine’s ultimate takeover of Rapture… and now, you must escape before he kills you!

(This midpoint comes in rather late in the game for a midpoint. Some might see another moment as the midpoint. But remember that the midpoint is defined as “the big twist that shows us what we’re really up against. The moment of truth, where everything changes.” And boy, does this fit the bill. Again, because a game is often an 8-hour minimum piece of entertainment, the plot points don’t have to line up exactly, and there are a lot more of them. You will find most game narratives follow the points outlined here, there’s just more time and more plot in between them.)

2nd Pinch Point

You escape to Dr. Tenenbaum’s safehouse. As a reward for helping the little sisters, she undoes some of Fontaine’s conditioning. When he realizes this, he raises the stakes by revealing he has more triggers than “would you kindly?” and uses one that makes your brain tell your heart to stop beating…

(This also reads like a 3rd plot point – a false victory followed by a low moment – but I labeled it as the 2nd pinch point because it sets up the 3rd plot point perfectly. You must find a remedy now or your heart will stop. Games contain more false victories followed by low moments than films do because that’s how the reward system works. You get a win, then something new goes wrong, giving you a new objective. This keeps you happy and playing.)

ACT 3

3rd Plot Point

False Victory: You find the Lot 192 remedy that undoes Fontaine’s mind control and arrive at Point Prometheus to face Fontaine! Low Moment: Fontaine escapes! He’s locked you out and there’s no way in…unless a little sister opens the doors for you.

You must collect the components to become a Big Daddy and trick the little sisters into opening the doors so you can get to Fontaine.

Climax

You fight Fontaine! And, once weak, the little sisters finish him off with their syringes!

The End

A cinematic shows that the little sisters all grow to have normal, happy lives because of you, and when you die of old age, they surround you on your deathbed, giving you the one thing you actually never had – a family.

LATEST NEWS

Blog

12.12.25

15-Year Retrospective - Part 4: Fifteen Years of Building, Learning, & Looking Ahead

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

As Blind Squirrel Games celebrates its 15th anniversary, the past few years have marked a period of bold transformation and resilience. From expanding BSG’s global footprint with the acquisition of Distributed Development in Colombia to balancing its legacy of ports and remasters with ambitious creative ventures, the studio has embraced change while staying true to its roots.

Blog

12.10.25

Scalability: How Blind Squirrel Meets Demanding Project Needs

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Great development cycles demand great planning. See how BSG forecasts staffing, welcomes new talent, and adapts as project scopes evolve.

12.08.25

Narrative Design Series Part 3: Pre-Production

Mimi Black, BSG Design Department

In Part 3 of our Narrative Design series, we talk pre-production: what is it, why is it important, and the lore bible deliverables for it.

Blog

12.01.25

15-Year Retrospective - Part 3: Boss Fights and Breakthroughs

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

By the late 2010s, Blind Squirrel was entering a pivotal era. After years of success with ports and remasters, the studio began charting a new course, one that would expand its creative ambitions and global footprint.

Blog

10.13.25

Narrative Design Series Part 2: Planning & Ideation

Mimi Black, BSG Design Department

In Part 2 of our Narrative Design series, we explore: what does a narrative development pipeline look like? The pipeline starts with planning and ideation, which is what we will explore here.

Events

09.23.25

BSG at NZGDC: Sharing Lessons, Sponsorship, Cosmorons

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

BSG at NZGDC 2025: Three Speakers, Sponsorship, and Cosmorons at Kiwi Games Zone!

Blog

08.12.25

15-Year Retrospective - Part 2: Leveling Up

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Between 2013 and 2016, Blind Squirrel Games evolved from a strike team studio into a full-fledged production powerhouse. This period saw the studio’s first big breakout with Bioshock: The Collection, the development of new business infrastructure, and its expansion to new industry partners. Hear from CEO Brad Hendricks, COO Matthew Fawcett, and Director of Project Management Office Drew Bradford on BSG’s expansion.

Blog

06.06.25

15-Year Retrospective - Part 1: The Spark

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

15-Year Retrospective - Part 1: The Spark In 2010, Brad Hendricks lost his job and bought a house in the same week. Most people might have panicked. Brad? He started a game studio.

Newsletter

03.07.25

Blind Squirrel Newsletter: Q1 2025

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Catch Us at GDC 2025 – New Studios, New Games, and More!

News

02.05.25

Colombian Studio Acquired by BSG

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

BSG has acquired Distributed Development, a Colombian game studio, to enhance its global presence and drive cost-efficient AAA game development.

News

12.05.24

Cosmorons Featured in Xbox Winter Game Fest 2024

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Cosmorons Featured in Xbox Winter Game Fest 2024

News

11.21.24

Blind Squirrel Games Announces Cosmorons, an All-New, Original Intergalactic Arcade Shooter

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Cosmorons: Now in development, players will blast into the cosmos to take on galaxies in pursuit of ‘Ultimate Glory’

News

10.11.24

CEO Brad Hendricks Interviewed on Game Dev Advice Podcast

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Brad dives into topics like starting your own studio, self-publishing, and more on the Game Dev Advice podcast!

News

06.13.24

Delta Force: Hawk Ops - Blind Squirrel Games Announces Involvement

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Blind Squirrel Partners with TiMi and Team Jade on New Delta Force: Hawk Ops Game

News

06.12.24

New World: Aeternum Consoles Release - Blind Squirrel Games Working Alongside Amazon Games

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Blind Squirrel Games Working Alongside Amazon Games on New World: Aeternum Console Release

News

06.11.24

State of Decay 3 - Blind Squirrel Games Named Co-Development Partner

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Blind Squirrel Games Named Co-Development Partner in State of Decay 3

News

05.07.24

New World: Winter Rune Forge Trial Deep Dive

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Join Environment Artist Carlos Lopez for a glimpse into how the Art Team brought our latest Seasonal Trial to life.

News

03.30.24

BSG Interview with Game File

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

CEO Brad Hendricks shares insights on publishing trends, forward-thinking development, and next-gen backwards compatibility.

Events

02.06.24

Blind Squirrel Games Sponsors DICE Summit 2024: Game Changers

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Blind Squirrel Games is a proud sponsor of DICE Summit 2024: Game Changers

News

01.12.24

BSG Interview with CanvasRebel

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Meet Brad Hendricks, the biggest trends emerging in your industry, leading creative teams, and more

News

01.10.24

2024 gaming industry predictions featuring BSG CEO Brad Hendricks

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

More AI, fewer risky bets, and finding footing in a changing industry: Industry professionals share their opinions of what may shape the games sector this year

News

09.08.23

Blind Squirrel Games Rebrands to Mark its Growth in Gaming

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Blind Squirrel Games Rebrands to Mark its Growth in Gaming

News

08.27.23

Blind Squirrel Games gives Keynote at NZGDC

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

BSG Gives NZGDC Keynote: Building a Better Workplace for Better Games

News

03.08.23

Brad Hendricks Gives Interview at DICE 2023

Blind Squirrel Games Admin

Las Vegas Review Journal Interviews Brad Hendricks on LAN Parties Podcast

We use cookies to improve your experience. By using this website you agree to our Cookie Policy.